How Native Advertising has further created promotional saturation in the UK.

Professor Aeron Davis said “Promotion appears everywhere, so much so that we no longer notice” and he begs the question “why does no-one ask much about our promotion-saturated world?” When one thinks properly about this question we really start to realise just how “bad” this “problem” has become. However does this really deserve the negative connotations it comes with? Is the promotional saturation a bad thing? What is the societal impact in the UK? These questions will all be discussed throughout this essay.

Native advertising is the epitome of disguised advertising; its exact function is to blend in with the surrounding content and the platform on which it is being shown. Although still a relatively new concept to those not familiar with the marketing world (maybe due to the fact that it can easily go unnoticed), Native Advertising is quickly becoming more and more ubiquitous, especially in the UK. Native Advertising does however have to follow guidelines from the Federal Trade Commissions (FTC.gov, 2018) which are there to prevent the customer from being deceived. Although the content is there to blend in with its platform, it must still be made clear that the content is paid for and is an advertisement.

“Paid advertising that mimics unpaid content is not new” (Hyman, 2017). The term Native Advertising was first coined by Fred Wilson in 2011 at the Online Media, Marketing, and Advertising Conference in 2011, (Wasserman, 2018) and has now become popular amongst brand strategists. It is something that businesses have started to use in order to create content that enables them to create meaningful connections with potential customers; increasing purchase intent and content views. It can often be seen through sites such as BuzzFeed, but although many may assume it is a modern-day creation, in reality America’s native advertising dates back to the late 19th century when John Deere published “The Furrow” to promote his products to farmers. However this technique wasn’t fully embraced in the UK until 2015, when the Telegraph Newspaper was the first to launch a native advertisement on Apple News through its campaign with Nikon (Campaignlive.co.uk, 2015).

With the emergence of web 2.0 the 21st century now provides an ideal environment for native advertising, as it is no longer constrained to radio or TV programmes. For example, Google and Yahoo have enabled businesses to promote their services and goods through search ads that automatically help them connect with their specific target audiences and customers, these are the “sponsored” links that come up first in your search results. You may not even notice that they are adverts. Buzzfeed also allows their brand partners to customise what goes into their articles and there is little difference between their sponsored articles and Buzzfeed’s normal posts; again, you may not even notice that they are promotional content. Although this is somewhat the point of native advertising, it does prove true that they often go unnoticed, which is not in line with the FTC’s guidelines.

Nelly Gocheva, the editor of T Brand Studio International, says that in order to create Native Advertising you must “first find the compelling story or a brand, then tell the story with journalistic expertise, before then delivering the story to the right people” (Gocheva, 2018). In order to find the story it is a “mining process that echoes the reported work of the newsroom” (IBID). She continues to say that native advertising can be more than just an article; they can include videos or VR (virtual reality) experiences. These types of marketing have been fully taken advantage of by companies such as Coca-Cola, HBO, and Nissan, and hence Video Advertising has been responsible for the highest source of revenue; growing at a 32% rate per year. Publishers therefore realise that this medium is a highly valuable way to create revenue from online traffic.

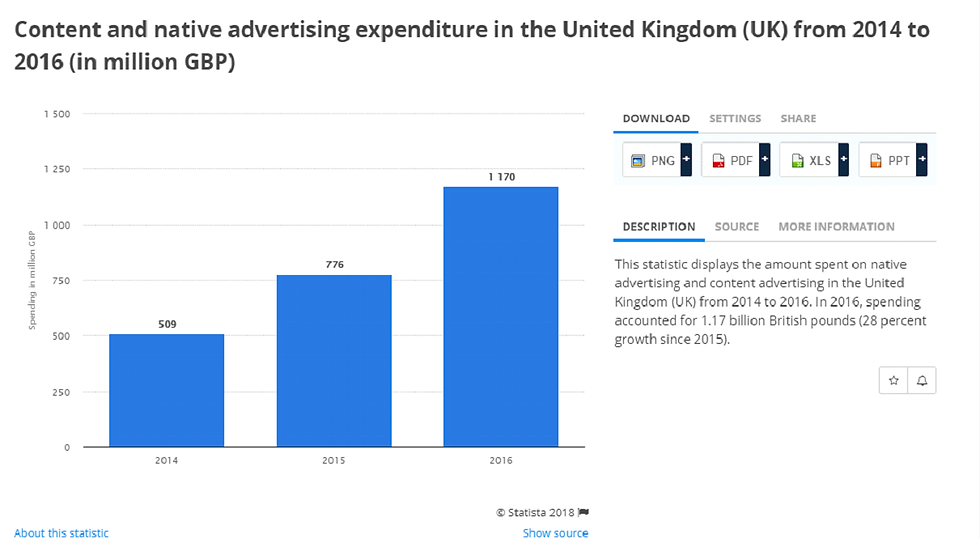

Marketers and agencies all over the world are now embracing Native Advertising due to its benefits like “stronger consumer engagement and better credibility with consumers” (Gocheva, 2018) with the ad spend on the format more than doubling between 2014 and 2016 (statista.com, 2018) (appendix 1) and this is only expected to grow.

With native advertising clearly becoming such a growing and lucrative format, adding to our promotionally saturated world, it is questionable as to why there are still so many grey areas around the labelling and clarity of the medium.

BuzzFeed is one content provider that makes the majority of its revenue from native advertising (Isaac, 2018.) Its paid for articles are almost exactly the same, in both content and style, as those that are un-sponsored. Although they adhere to the guidelines from FTC by including a “brand publisher” box and logo at the top, they can still be easily read as normal BuzzFeed articles (Constine, 2018). A point worth noting is that buzzfeed.com does not have many site views in itself when compared to its content’s views; the majority of its content is shared on other social media platforms such as Facebook. This works to make its sponsored articles appear even more diluted; by this I mean they are often shared or people get “tagged” in them and so if the posts that appear on your newsfeed are there because a friend has shared it or been tagged in it, then you are probably more likely to trust it and read it than if this was not the case.

Instagram is another social media platform that often features sponsored posts, however some of these are seen as deceiving and misleading. According to FTC (2016) Lord & Taylor, a national retailer, had to pay charges to the commission after it was proven that they had “deceived consumers by paying for native advertisements (including an Instagram post by Nylon) without disclosing that the posts actually were paid promotions”. This is just one of many cases where a brand was paying online influencers to promote their product, without making it clear it was a promotion to the consumer. These online influencers will be paid, or often just given the product for free, in return for posting it online and telling their following about it. If it is not made clear that these adverts are paid for then it goes against the FTC guidelines. This further iterates the fine line that companies must tread to ensure they are promoting their goods in a fair and non-deceiving way. Holmes (2014) said that native advertising "is designed to fool readers into thinking they've read a normal news story, written truthfully and independently, when in reality it's tainted by the agenda of the brand that paid for it”, and this is exactly the trap that Lord & Taylor lead its consumers into. But this brand is not alone, “if the Federal Trade Commission decided to audit publishers' native ads today, around 70 percent of websites wouldn't be compliant with the FTC's latest guidelines, according to a new report from MediaRadar” (Swant, 2018).

The main reason for these guidelines is trust; consumers need to be aware that advertisements are exactly that, and not just unbiased reviews. This will also work to the advantage of the companies if they follow these guidelines, as people who later find out they have been lied to are likely to lose trust in the brand; “the bottom line consequence of poorly executed Native Advertising campaigns can result in lower purchase intentions from consumers” (Becker-Olsen, 2003). It appears that one company may have already realised this. Facebook has recently launched a news feed update (already launched in America but soon to be rolled out internationally which will mean that “publications deemed more trustworthy may see an increase in distribution” (Dickey, 2018). Mark Zuckerberg said that “it will shift the balance of news you see towards sources that are determined to be trusted by the community.” After analysing the results of my survey it seems to me that this update is perfectly timed as it seems that youth, the main users of social media such as Facebook, are growing less and less trusting of promotional content and its publishers. However, although this may appear to be an update working in the eyes of the users, in reality could this not just be another way of optimizing content views for larger “more trusted” organisations and minimizing views for independents? When a similar update happened to Instagram some smaller organisations wrote to the platform asking for it to return to its previous chronological format, in order to give them a fair chance of gaining content views (Group, 2018).

After looking at native advertising and how it is deeply embedded into social media in the UK, I conducted a small survey myself to see if I could bring anything new or even contradictory to light about the societal impact of native advertising in the UK. I created a survey using the free online provider called Kwiksurvey, and sent the link to friends, relatives, and asked them to then further pass on the link. After receiving 105 result I delved into looking at the results.

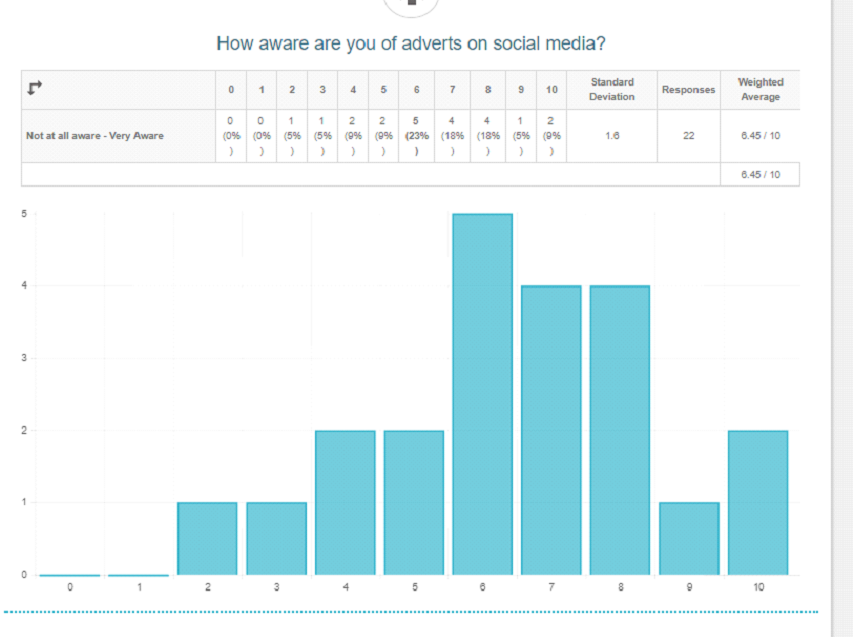

One of the questions asked was “Are you aware of the term native advertising?” I split the results into those who answered yes and those who answered know, and then compared these two groups’ answers to the question “How aware are you of adverts on social media?” Those who answered yes to the native advertising question appeared to be much more aware of adverts on social media (appendix 2), and in turn those who hadn’t heard of it seemed significantly less aware of advertisements on social media (appendix 3). This suggests that hearing about native advertising may have caused them to be more aware of advertising in general, especially as a lot of native advertising features on social media.

Next I looked at the people who had heard of native advertising’s answers to the question “how clearly labelled do you think advertisements are?” This group seemed to think they weren’t clearly labelled at all (appendix 4), whereas those who hadn’t heard of native advertising however are mainly situated much closer to the “neutral” section of the Likert scale (scale of 0-10, 0 was “not clear at all- it is misleading” and 10 was “very clear”), answering mainly with 4s, 5s, and 6s (appendix 5). This seems to suggest that people who are aware of native advertising, and the fact that the whole point of it is to blend in, may consider this to be an unsatisfactory level of clarity and assume that its purpose is to mislead the viewer.

On top of this, the 22 respondents who said they had heard of native advertising answered more negatively to the question “is your view of advertising negative or positive?” (appendix 6) and those who didn’t know about native advertising answered more positively (appendix 7) . Even though a score of 4 on the Likert scale of 0-10 (0= negative, 10= positive) was the most common response on with both groups, the latter was more heavily weighted to the positive end, with one some 10 and 8 responses. This works to again suggest that native advertising is something that people do not like the idea of; those who do not know about it seem to be more open and happy about advertising.

A final thing worth noting from looking at the results of this survey is that, although there were only 14 respondents in the 46-60 age group, when they were asked “Is your view of advertising negative or positive?” all answers fell in either 4, 5 or 6 (appendix 8). However although the 14-24 age group’s answers included both positive and negative responses, they included much more 0s and 1s than 9s and 10s (appendix 9). This could suggest that the older generation are either oblivious to, or do not feel affected by, our promotionally saturated world, however the younger demographic are often the ones targeted and affected more by advertisements, causing them to have a negative view of advertisements and promotional material from an early age.

President of the Marketing Firm Yankelovich, Jay Walker-Smith told CBS news in 2006 that we now see around 5000 adverts per day (cbsnew.com), however in my survey of 104 respondents, only 1 thought they saw more than 500 each day (appendix 10). This shows just how unaware and naïve we are; advertisements attack our subconscious.

In conclusion, from my own research and from that of others, it appears to me that not only is the UK extremely promotionally saturated, the public are not happy about it. We have lived in a world where we are continually bombarded with adverts for decades now, however promotional material is no longer just something found between television shows or songs on the radio. I feels like we are being fed adverts without even realising it, and even though it doesn’t appear to be something that the public wants, nothing/ very little is being done to prevent it. Adverts are not clearly labelled (in the eye of the public), as seen from the results of my survey. Although these native advertisements may be in line with the FTC guidelines, they are still misleading people into believing that a publisher that they trust is recommending a product, and not necessarily being paid to do so. It is true to be said that the younger generation are becoming more aware of these formats of advertisement, however I still do not believe this to be good enough.

References

Becker-Olsen, K.L., 2003. And now, a word from our sponsor--a look at the effects of sponsored content and banner advertising. Journal of Advertising, 32(2), pp.17-32.

Campaignlive.co.uk. (2018). Telegraph launches first UK newspaper native ad on Apple News. [online] Available at: https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/telegraph-launches-first-uk-newspaper-native-ad-apple-news/1371857 [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].

Cbsnews.com (2018) Cutting Through Advertising Clutter [online] Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cutting-through-advertising-clutter [Accessed 24 Jan. 2018]

Constine, J. (2018). BuzzFeed’s Future Depends On Convincing Us Ads Aren’t Ads. [online] TechCrunch. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2014/08/12/buzzhome/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2018].

Dickey, M. (2018). Facebook’s latest News Feed update will prioritize trustworthy publishers. [online] TechCrunch. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2018/01/19/facebooks-news-feed-update-trusted-sources/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2018]

Federal Trade Commission. (2016). Lord & Taylor Settles FTC Charges It Deceived Consumers Through Paid Article in an Online Fashion Magazine and Paid Instagram Posts by 50 “Fashion Influencers”. [online] Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2016/03/lord-taylor-settles-ftc-charges-it-deceived-consumers-through [Accessed 22 Jan. 2018].

Ftc.gov. (2018).Federal Trade Commission Guidelines . [online] Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/896923/151222deceptiveenforcement.pdf [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].

Group, D. (2018). Small businesses fight to keep Instagram chronological |DAC UK. [online] DAC UK. Available at: https://www.dacgroup.com/en-gb/small-businesses-fight-to-keep-instagram-chronological/ [Acccessed 23 Jan. 2018]

Hyman, D.A., Franklyn, D., Yee, C. and Rahmati, M., 2017. Going Native: Can Consumers Recognize Native Advertising: Does It Matter. Yale JL & Tech., 19, p.77.

Isaac, M. (2018). 50 Million New Reasons BuzzFeed Wants to Take Its Content Far Beyond Lists. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/11/technology/a-move-to-go-beyond-lists-for-content-at-buzzfeed.html [Accessed 23 Jan. 2018].

Statista. (2018) Native advertising spending in the UK 2014-2016| Statistic. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/536205/native-ad-spending-in-the-uk/ [Accessed 22 Jan. 2018]

Swant, M. (2018). Publishers Are Largely Not Following the FTC's Native Ad Guidelines. [online] Adweek.com. 2018].

Wasserman, T. (2018) What is ‘Native Advertising’? Depends who you ask. [online] Mashable. Available at: https://mashable.com/2012/09/25/native-advertising/#.qNWLtDFaGqu [Accessed 22 Jan. 2018]

Appendix

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

Appendix 9

Appendix 10